Are Banks Afraid to Enter the Repo Market Like in 2008?

The Federal Reserve stepped into the repo market last week to control soaring interest rates. How will this affect the major banks? | Image: Johannes EISELE / AFP

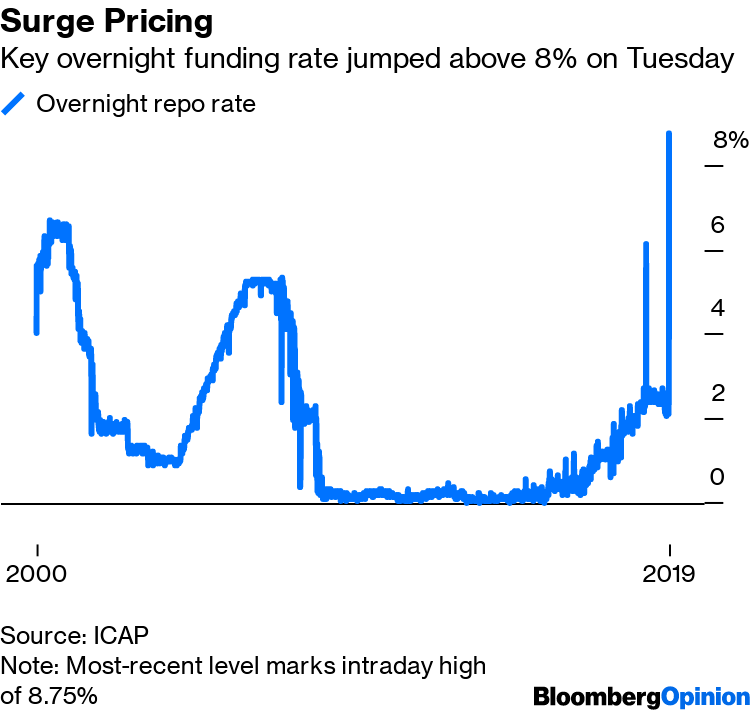

Last week’s panic in the repo market resurrected images of a possible 2008 economic meltdown. That was when banks stepped away from the bourse causing Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns to collapse.

This obscure yet essential aspect of the U.S. financial system often runs smoothly in the background that it is often overlooked. It involves a short-term loan agreement between the dealer (borrower) and the counterparty (buyer). The dealer sells securities usually in the form of U.S. Treasury notes. The counterparty, such as mutual funds and large corporations, buys the bonds with the expectation that the borrower will repurchase them the next business day with modest interest.

This is how the $2.2 trillion marketplace operates.

More often than not, there are enough funds in the system that the repo market operates as expected. Last week, however, a confluence of events involving quarterly tax bill payments and the settlement of U.S. Treasury bills depleted the reserves for financing. As a result, the Federal Reserve had to step in to keep repo rates from spiraling out of control.

Many thought that the intervention would be a quick fix. However, the Fed announced that it plans to soothe the repo market until the end of the quarter. According to Fortune, the Fed requires a massive $400 billion bailout to achieve the “appropriate level of reserves.”

The prolonged intervention, as well as the amount needed to fix the leaking market, are leaving many investors with more questions than answers. Has liquidity actually dried up or are banks stepping away from the repo market just like they did in 2008?

Banks are Highly Liquid

To answer the first question, banks have a lot of cash parked at the Fed as reserves. ZeroHedge reported that banks have $1.4 trillion dollars in excess cash deposited at the Fed.

If banks are highly liquid, then why did they fail to take out their reserves to support a repo market that’s under duress? It appears that Fed officials are asking the same question.

According to the Financial Times , the New York Fed is “looking at why cash failed to move from banks’ accounts at the Fed into the repo market, where banks and investors borrow money in exchange for Treasuries to cover short-term funding needs.”

We spoke to economist and trader Alex Kruger and asked why banks did not respond to the crisis given that they have the liquidity to do so. The economist replied,

It‘s because of [the] Basel regulations.

According to Mr. Kruger, banks now need way more reserves than what the reserves requirement indicates. The economist also said,

In other words, what is known as Excess Reserves (reserves over required reserves) is now a misnomer. A key factor is that now only the banks know how much reserves are ideal for their operations. That is specific to each bank and based on private information.

In addition, Kruger stressed that the Fed is in the dark with regard to the amount of reserves required by each bank. He also said,

The Fed can’t know anymore because of banking regulations. The end data was never set in stone. The Fed was waiting for feedback from the market to decide. The Fed got a lot of feedback from the market in the form of prices.

Thus, with the Basel regulations in play, banks have to meet their own reserve requirements before thinking of entering the repo market.

Banks Have More Directives to Consider

On top of the Basel regulations, banks also have to take into account the Volcker Rule, said Kruger. He stressed,

The Volcker Rule forced banks to reduce risk-taking. Reduced leveraged risk-taking leads to reduced arbitrage and reduced liquidity. The spike in rates would have been considerably smaller in the absence of the Volcker Rule as more risk-takers would have stepped in to take advantage of the spike.

In a nutshell, the Volcker Rule prohibits banks from tapping into customer deposits to own, invest or sponsor private equity funds and hedge funds. In short, they can’t use their own customers’ money for trading operations.

The presence of this rule helps explain why banks kept their reserves parked at the Fed with 1.8% interest instead of exploiting the surging repo rates that went as high as 8.75% last Tuesday.

In the end, banks are not afraid of the repo markets like they were in 2008. However, it would appear that last week’s panic was heightened by two post-global financial crisis regulations. While the Fed tries to figure out how to distribute idle assets, it will continue running open market operations.